By Diane Cameron for the Montgomery Countryside Alliance

September 7, 2020

To make successful rural policy, we must center rural people.

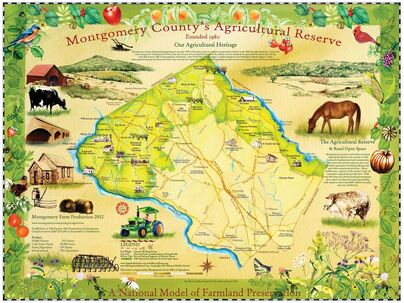

The COVID pandemic, on top of structural racism and economic inequity, has worsened the problem of hunger in Montgomery County. To answer the need for local food affordable to low-income residents, our own Agricultural Reserve – one third of our County’s land area – holds the potential to become a major supplier of table crops to Montgomery County and the greater Washington, D.C. region. Manna Food Center is an example of an organization working with Ag Reserve farmers to supply fresh fruits and vegetables to low-income families.

The proposal’s backers believe their proposal is modest, as its stated target of 1800 acres amounts to two percent of the Ag Reserve’s total of 93,000 acres. Other observers note that Governor Hogan’s statewide task force report on solar development that the two percent target comes from, actually targets much more land here; they say it targets at least 12,000 acres of Montgomery’s Ag Reserve for the photovoltaic arrays totaling 2,500 MW, so the ZTA’s two percent is only the first step. The solar-electricity proponents point to pilot projects in other states where pollinator-friendly plants like milkweed grow beneath the solar arrays. As for the compatibility of large-scale commercial solar with the economics of farming including for table crop production, there are many unanswered questions.

So far, no one has studied in depth the long-term effect this major land use change would have on the economy of the Ag Reserve, including how many tenant farmers would lose their leases as landowners go for the larger cash flows from the solar arrays. Reports from farmers and Ag Reserve advocates show a tenfold or greater increase in annual rent that the solar developers are paying (a reported $1700/acre), compared with the rents that tenant farmers are now paying (for instance one farmer growing commodity crops in the Ag Reserve now pays $120/acre). The potential ripple effect into the economy of the Ag Reserve is large, as other non-solarizing landowners are likely to raise their own rates, driven up by the rents that the solar developers are willing to pay. There’s a similar lack of local studies showing how this proposed solar boom will affect young and immigrant farmers seeking to start new farms in the Ag Reserve, and whether they’d be able to obtain long-term leases at rents that fall within their budgets.

Council Staff reviewed the records surrounding ZTA 20-01. They found a total of 842 records. (is yours one of them? Take action here)

There are at least 72% who have weighed in against or concerned with the Solar ZTA 20-01.

The responses, from councilmembers and solar industry allies have danced around the edges and avoided addressing the land rent problem. The solar boosters have ignored the fundamentals of land economics, and glossed over the effect of commercial solar leases on the farming economy driven by land rents and land prices. At stake is the ability of existing farmers to remain viable, and of new farmers to enter the Reserve and grow their production of food for the region’s tables.

Given these uncertainties, big communication gaps, and potential for major shrinkage of land access to farmers, farmers and Ag Reserve advocates are demanding that the Council say No to this proposed ZTA, and that it delay its work on this issue until after the pandemic is over, and in-person meetings can resume. Let’s not rush headlong into this momentous decision. Let’s set the table for an informed conversation on the future of our rural economy in the Ag Reserve – a conversation that centers rural people and new and immigrant farmers who want to supply food to our region.

Hunger is a reality for an increasing number of Montgomery’s residents. For low-income families, seniors, and people with disabilities, food insufficiency was already a fact of life before the COVID-19 pandemic. With a surge in demand for food banks during the pandemic, the number of people who struggle with the terrible choice of “pay rent or buy groceries” is estimated to have doubled locally and nationwide.

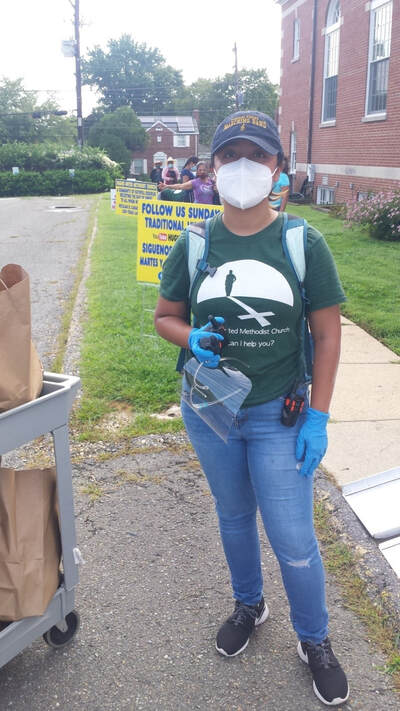

Montgomery County government is partnering with churches and other non-profits, and local farmers, to meet this need. Aranza Gasca, Manager for the Hughes United Methodist Church food distribution program in Wheaton, was directing volunteers this past Thursday to prepare to give food boxes to 500 families. This is one of 38 non-profits who are receiving financial support from Montgomery County, through the Food Council in order to feed low-income families.

| As I walked back from the church just before the September 3rd food give-away began, I passed over 300 cars lined up for seven blocks into the neighborhood behind the church. Not everyone can afford to drive a car. On Tuesdays, Ms. Gasca told me that fresh fruits and vegetables are distributed, and volunteers with cars are needed to drive the food to families who lack access to a car – and “who would have to take two buses to get here” as Ms. Gasca described their dilemma. For information on a food distribution center near you – including to volunteer to be a food driver for residents who can’t drive to one of these centers click here. Food from far away is increasingly scarce - and expensive. Due to the COVID pandemic causing increased food prices and economic shrinkage as people lose their jobs, families are experiencing more hunger than ever before – and demands for assistance from local food banks are surging. Before the pandemic, Manna reported that “…approximately 63,000 of Montgomery County residents do not know where their next meal will come from.” |

With food prices increasing due to COVID-related supply disruptions, and crop outputs and prices uncertain due to drought cycles intensified by climate disruption, many are looking to increase local food production, and to provide this local food to the tables of the most-needy families.

The County’s food distribution program includes fruits and vegetables grown in Montgomery’s Agricultural Reserve, and Ag leaders are working to put more locally-grown produce on local tables. Jeremy Criss, Director of the County’s Office of Agriculture, said “We are working to get more farmers to grow more food in wholesale production – in the Ag Reserve.” Criss described his work with local farmers and orchardists to supply produce to the Manna Food Center’s Farm to Food Bank Program. Six local producers are now signed up, including Lewis Orchards and Butler Orchards. “We hope to get more Ag Reserve farmers into this program. Now is not the time to be taking farmland out of production for solar fields,” noted Criss.

Land access – encompassing identifying parcels suitable for farming, and then obtaining a lease or sale that’s affordable and sustainable - is the first priority need for farmers whether they are beginners, or seasoned producers. Farmland and forested land in the Ag Reserve is inexpensive for a reason – the county has preserved this land for farming, forests, and open space, designating the Agricultural Reserve zone (AR zone) for one dwelling unit per 25 acres. That commercial developers from the solar industry are hungry for this low-cost land is not surprising. That the county council is working to grant them this unprecedented access, is concerning to many residents and farmers alike – including to many climate change advocates. Montgomery Countryside Alliance is one of several organizations who have issued action alerts in opposition to ZA 20-01, and the Alliance has counted over 700 unique emails from county residents sent to the Council over the past few months.

Even with a council decision pending, solar companies are already peppering local landowners with offers of high rates for renting farm fields. Lauren Greenberger, President of Sugarloaf Citizens Association notes, "I and many other landowners and producers have already received multiple offers to lease my land at prices way above current farm rental rates. There was no mention of community solar, agrivoltaics or Pollinator Habitats in their offers."

In 2017, the National Young Farmers Coalition surveyed more than 3,500 young farmers and ranchers across the country and found that, “…regardless of geography or whether they had grown up on a farm, land access was their number one challenge. In particular, farmers reported struggling to find land to buy or rent that was affordable on a farming income, that had the appropriate resources for their operations, and that had housing opportunities. Twenty-eight percent of respondents who cited land access as a challenge, felt insecure and worried that they would lose their access to land.”

The Land Link program of Montgomery Countryside Alliance is designed to meet the expanding need for land access, matching up farmers who seek to farm here, with local land owners seeking lease arrangements. “Over the past six weeks, MCA has received four new Land Link requests – two from new farmers from Africa seeking to farm here, and one from an African-American farmer. We are now engaged in helping them to find the type of land they require for the crops and other products that they plan to produce. Part of this process in Land Link - the land search and the match-making of farmers and landowners, depends heavily upon land prices and rents. Keeping the land prices and rents affordable to all farmers, and especially to these beginning farmers, is critical,” says Caroline Taylor, Executive Director of the Montgomery Countryside Alliance. Caroline points to two Land Link success stories of African immigrants finding land on which to farm in Montgomery County – Dodo Farms in Brookeville, and Passion to Seed Farm in Olney.

Beyond the fundamental economic conflict of large-scale solar versus farming requirements for affordable land access, farmers and ranchers have practical concerns about compatibility. In a meeting with Montgomery Planning Department Director Gwen Wright last October, Lee Langstaff, livestock farmer and Board President for Montgomery Countryside Alliance, reflects on the stated opportunities for co-locating commercial agriculture with commercial solar facilities: “What if I need to re-seed or plant more diverse pasture forage for my sheep? How do I maneuver my tractor and attached equipment in and around a solar installation? What about mowing and weed control? And how do I feed big round bales of hay in the winter? The logistics of agricultural activity in conjunction with large solar installations (particularly the much touted grazing of sheep under the panels) just don’t make sense here.”

Agrivoltaics is the newly emerging combination of farming and commercial solar arrays. Its promoters acknowledge that they’re still in the learning phase of this technique. While there have been pilot projects around the country, this is untested locally, and not ready for commercial scale. The economic conflict between the rents that farmers are able to pay versus the rents from solar companies, puts the farmer at a strong disadvantage, even where a crop or livestock operation has worked out the practical compatibility of navigating their equipment around the physical structure of the arrays. Given the solar industry’s deep pockets, wherever a practical conflict arises that must be negotiated with the landowner and/or solar tenant, it’s unlikely that the resolution will favor the farmer.

Under the 1980 Agricultural Reserve Master Plan, farming is essential to the “preservation of regional food supplies.” The deployment of commercial solar in an area master planned, zoned, and preserved for farming, undermines the Reserve’s very purpose, by presenting insurmountable economic challenges for both existing and new producers seeking to lease or buy reasonably-affordable farm acreage.

This is the choice now before the County Council: Help local farmers, including new farmers of color, to step up production of table crops and other food and fiber products for our region, enabling us to supply local produce to low-income families – or help solar developers access cheap land to produce electricity at commercial scale. We can’t do both, so we must choose. While we can locate solar arrays in smart-growth locations – already disturbed or developed land, including parking lots, industrial sites, and large rooftops – we cannot create more farmland and forest land.

Our response to the climate crisis doesn’t mean we should change the purpose of our Agricultural Reserve and upend the agricultural zoning approach that we created over decades, that has enabled farmers to keep farming. Despite the narrow focus on solar electrical generation by Councilmember Riemer, other councilmembers, and Sierra Club representatives, Montgomery’s climate emergency response includes hundreds of recommended actions from six expert panels; the Ag Reserve plays a critical role in the recommendations of the Carbon Sequestration and Climate Adaptation panel reports.

While solar industry representatives say that it’s more expensive to site solar arrays in urban areas, promoting and enabling commercial-scale solar in the Ag Reserve results in significant expense from a public perspective. Enabling solar developers to access cheap land in our Ag Reserve amounts to a large County subsidy to the solar industry – changing and challenging the central purpose of the Ag Reserve Master Plan. This change would put farmers at a distinct economic disadvantage in favor of energy production. Both local farming and solar energy have climate benefits, and solar arrays can be located in urban areas, but we must maintain the Ag Reserve for agriculture. We must implement the prescient Ag Reserve Master Plan in order to protect our forests and farms, continue to help new and immigrant farmers access land here, and to profitably grow their access to local markets. In order to grow our regional food supply and put food on the table for low-income residents, we must step-up our support for new and existing farmers – and say no to non-compatible uses including commercial-scale solar.